Pathologist’s Corner – Dr. Summerall’s on A Patient’s Guide to Colon Cancer and Lynch Syndrome /HPNCC

Published: March 24, 2015 – Dr. Janna M. Summerall

Introduction

Introduction

March is National Colorectal Cancer Awareness Month. Each year, over 140,000 people are diagnosed with colorectal cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute. It is the second most commonly diagnosed type of cancer when men and women are combined. Because of increased surveillance and more effective treatment, deaths from colon cancer are steadily declining. Discoveries in genetics have lead to a greater understanding of the genetic basis of colon cancer, and the discovery of inherited cancer syndromes. Now, in some cases, people may be discovered through genetic testing to have an increased risk of developing colon cancers. These individuals can be closely monitored for early signs of cancer. If discovered, they can be treated early, before the cancer grows large or spreads.

Causes of Colon Cancer

The vast majority of colon cancers are sporadic, meaning their exact cause is unknown. Risk factors that increase the possibility of developing colon cancer include obesity, smoking, heavy drinking, a sedentary lifestyle, and a history of polyps on earlier colon screening examinations.

Approximately 5-10% of colon cancers, however, are caused by known inherited genetic mutations. These inherited genetic syndromes cause a very high incidence of colon cancers in affected individuals, and can predispose them to other types of cancer.

Hereditary Colon Cancer

Some genetic mutations—the polyposis syndromes– cause the formation of numerous pre-cancerous polyps. Some of these polyps progress to cancer. Other genetic mutations do not predispose individuals to the development of polyps, but lead to colon cancer. One of these genetic mutations leads to a cancer syndrome called Lynch Syndrome, also known as Hereditary Non Polyposis Colon Cancer Syndrome (HPNCC).

Lynch Syndrome/Hereditary Non Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HPNCC)

The familial non-polyposis cancer syndrome was first discovered in the early 1900’s, and named after Dr. Henry Lynch, who continued this early study of families with inherited colon cancers. The genetic defect that causes Lynch Syndrome was discovered in the 1990’s.

About 5% of all people who have colon cancer are thought to have Lynch Syndrome. Patients with Lynch Syndrome have a 60-80% risk of developing colorectal cancer in their lifetime.

The genetic mutation that is responsible for Lynch Syndrome causes a defect in a protein that recognizes and corrects errors in DNA replication during the process of cell division. If these mistakes are not detected and corrected, then cells may develop problems with growth and division. These cells may be more likely to grow uncontrollably, leading to cancers.

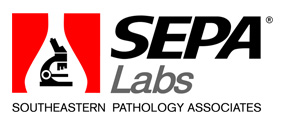

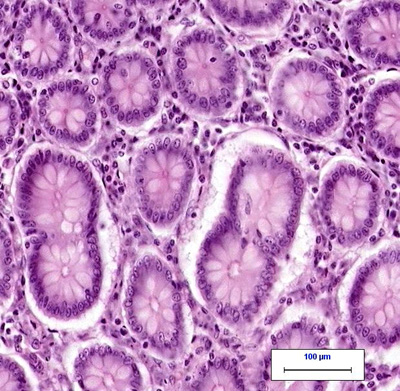

(Left: normal colon tissue under the microscope. Right: colon cancer under the microscope. From CAP: MyBiopsy)

Characteristics of Lynch Syndrome/HNPCC

Unlike the polyposis syndromes, in which a patient may develop thousands of polyps, very few polyps develop in patients with Lynch syndrome. However, these polyps can progress to cancer much more rapidly than in other patients. Patients with Lynch Syndrome develop colon cancers at a younger age than those with sporadic colon cancers.

Along with a high incidence of colorectal cancer, patients with Lynch Syndrome can develop tumors in other sites, including endometrium, ovary, stomach, urinary tract, biliary tract, pancreas, small bowel, brain and skin. The risk of endometrial cancer in women with Lynch Syndrome is particularly high, and the cancer usually develops at a slightly younger age than sporadic cancers.

Features That Suggest Lynch Syndrome/HNPCC

Based on a careful clinical history, a physician may suspect that a patient with colon cancer has Lynch Syndrome. An individual may be suspected to have Lynch Syndrome if:

- At least three family members have a Lynch Syndrome-associated cancer, two of which are first-degree relatives.

- At least two generations are represented.

- At least 1 individual was younger than 50 years at diagnosis.

Under the microscope, colon cancers caused by Lynch syndrome have features that are different than sporadic colon cancers. Inflammatory cells may surround the cancer cells; they may produce large amounts of mucus or may be poorly differentiated (have features that do not resemble the normal colon cancer tissue).

Testing for Lynch Syndrome

If Lynch syndrome is suspected from either the patient’s history, or because of the appearance of the cancer under the microscope, then genetic testing can be performed.

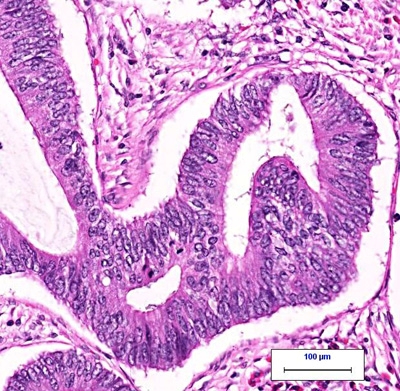

A patient’s cancer tissue can be stained with a special stain that binds to the cells’ DNA repair proteins. If the special stain demonstrates staining in the tumor tissue, then the DNA repair protein is being produced by the tumor and Lynch Syndrome is unlikely. If the tumor does not stain for one or more of these proteins, than the likelihood of Lynch Syndrome is high, and further genetic blood testing may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

(Colon cancer without the Lynch Syndrome mutation; the stain turns the normal proteins in the tumor cells brown.)

Consequences of Lynch Syndrome Diagnosis

A new diagnosis of Lynch Syndrome can have important consequences for a patient with colon cancer. The patient will be screened very frequently in order to detect the formation of additional colon cancers. They will be monitored for signs or symptoms of other types of cancers common in Lynch Syndrome patients—especially endometrial cancers in women.

The genetic mutation that causes Lynch Syndrome is passed from a parent’s chromosome to a child’s chromosomes. The genetic defect is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and the chance of a parent with Lynch Syndrome having a child with the genetic defect is 50%. Lynch syndrome affects both male and female children equally.

If an individual is found to have Lynch Syndrome, other family members will be offered genetic blood testing for Lynch Syndrome. If other family members are found to have Lynch Syndrome, they will be carefully monitored for the development of colon and other cancers.

Interestingly, patients with colon cancers caused by the mutation that causes Lynch Syndrome have better overall survival than those without the mutation. However, these tumors may also respond differently to chemotherapy drugs normally given to patients with colon cancer, although more studies are underway to determine this (reference).

SEPA Lab’s Role in Diagnosis Colon Cancer and Lynch Syndrome

SEPA currently offers special staining to detect Lynch Syndrome in cancer tissue. After making the initial diagnosis of colon cancer, a SEPA pathologist will look for features that suggest the possibility of Lynch Syndrome, and recommend special staining to look for Lynch Syndrome. The patient’s referring doctor can also directly request special stain testing for Lynch Syndrome on a patient’s tissue.

References

Patient education: Lynch Syndrome https://www4.mdanderson.org/pe/index.cfm?pageName=opendoc&docid=2133

Colon: adenocarcinoma http://www.cap.org/apps/docs/reference/myBiopsy/colon_adenocarcinoma.html

Emerging concepts in colorectal carcinoma: Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Retrieved from http://www.cap.org.

Colorectal Cancer. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/detailedguide/inde

[no_toc]